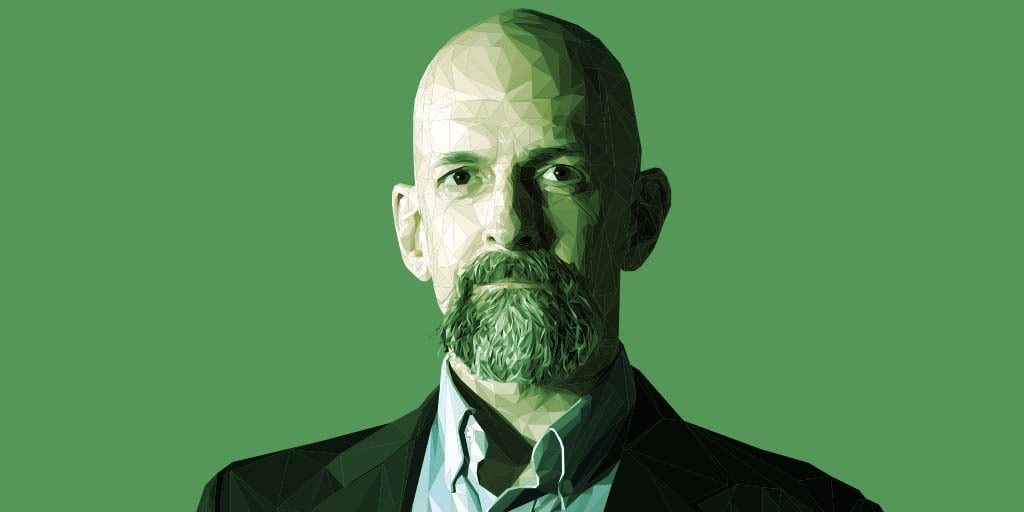

Neal Stephenson coined the word “metaverse” in his seminal 1992 sci-fi novel Snow Crash. 30 years later, Sotheby’s is auctioning off rare items associated with the book, and Stephenson is working on a new layer-1 blockchain company for the metaverse, Lamina1. The company’s stated purpose is to help creators build the “open metaverse,” the term Stephenson says he uses to differentiate it from the current corporate versions of metaverse.

Calling it an “open” metaverse, Stephenson said on the latest episode of Decrypt‘s gm podcast, “works pretty well. I think people understand the way it works: companies latch on to a word and use it for their purposes in a way that helps them achieve their goals as a business, and and it’s left up to we as consumers to kind of look at that and hopefully cast a skeptical eye on it.”

So, what is the open metaverse, and what isn’t it?

Stephenson said there are two main things that people get wrong, in his view, when they talk about the metaverse these days.

One mistake people make, Stephenson said, is “to talk about a metaverse, or multiple metaverses, which I think is wrong, that’s always a signal to me that somebody doesn’t get it.” In Stephenson’s view, there’s one metaverse, like the one internet, and companies creating closed metaverse environs aren’t getting it.

That’s not to say that there won’t continue to be games that are closed realms. Stephenson said game designers who create “coherent worlds that are exquisitely crafted” aren’t about to make their games completely open realms where you can bring a digital item from some entirely different game. “If somebody brings a sniper rifle into my soccer game, or whatever, it’s just an abomination from an aesthetic point of view, and it shows disrespect for what I do as an art director or a game designer,” Stephenson said. “I hope that games will continue to exist as pure works of art, just just like they are now. But there are also games, very popular games, that aesthetically are mashups, right?”

His examples of such games: Fortnite, Minecraft, and Roblox—games that have a “mashup kind of feel, which I think is a much closer match for the spirit of the metaverse as described in Snow Crash.”

Another mistake people make is “to assume that it’s always about using goggles, which is a reasonable assumption,” Stephenson said. “I mean, that’s how it is in the book and in other depictions of virtual reality and fiction. It seemed like a logical assumption at the time that that would be the the output device. But that’s not what happened. What happened is that everyone is accessing these 3D worlds through through two-dimensional flat rectangles on flat screens. And that works really well. In some ways, it works better than using goggles, for various reasons.”

Stephenson isn’t saying no one will make and sell VR headsets. Apple’s highly anticipated mixed-reality headset is coming soon. “To be clear, I’m not anti headset,” Stephenson cautioned. “I know people who who build those things for a living and their capabilities are amazing and getting better all the time. It’s just that you have to look at the reality of how people access these things. Today, you can’t spend tens or hundreds of millions of dollars making an experience that can only be be be used by the tiny minority of people who own these things. So you’ve got to make it work on flat screens as well.”

Listen to the full episode and subscribe to the gm podcast.