In this study, a mixed-methods approach was used, and it encompassed two consecutive phases: a preliminary qualitative analysis and a subsequent quantitative investigation. The mixed-methods framework leverages the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative methodologies. This approach produces outcomes that are more comprehensive and reliable. It ensures that the findings are well supported by diverse forms of evidence (Venkatesh et al., 2013). Qualitative research methodologies are employed primarily for exploratory purposes, enabling the generation of novel theoretical insights, fostering a profound understanding of phenomena, and facilitating the formulation of hypotheses (Cheng et al., 2020). Quantitative methodologies are predominantly utilized in confirmatory research, aimed at the empirical testing of theoretical propositions and causal relationships (Venkatesh et al., 2013).

Considering the nascent stage of research on the acceptance of digital exhibitions within the metaverse, mixed methods are particularly appropriate. This approach facilitates a thorough investigation of the variables influencing consumer acceptance, which is crucial given the limited literature on this topic. Combining qualitative interviews and quantitative analyses ensures that this study captures the complexity of consumer attitudes while also providing statistically robust conclusions.

Through qualitative enquiry, this study aims to explore the factors shaping consumers’ attitudes and behaviours concerning digital exhibitions within the dynamic landscape of the metaverse. Following qualitative research, PLS-SEM and fsQCA were employed to further strengthen the study. The convenience sampling approach to medium sample sizes it is used to evaluate the complex associations among observable and latent variables (Hair et al., 2020). Then, fsQCA is employed to identify patterns and combinations of elements that result in high or low acceptance levels, offering nuanced insights that traditional quantitative methods might overlook (Navarro-García et al., 2024).

Study 1: qualitative study

Data collection

Through semi-structured interviews, we gathered qualitative data to determine the variables that affect consumers’ receptivity to digital exhibitions within the metaverse. The design of the interview encompassed four principal components. Initially, the participants were invited to convey their overarching impressions of digital exhibitions. We subsequently delved into specific factors that the participants believed would influence their willingness to accept and engage with digital exhibitions. The participants were then invited to share their preferences for the nature of digital exhibitions and any particular features that they found appealing or off-putting. Finally, open-ended questions were posed to capture a wide range of perspectives on digital exhibitions. To mitigate potential information bias, several precautions were taken. The interview questions were designed to be structured, granting trained interviewers the flexibility to conduct more in-depth probing on the basis of the participants’ responses, particularly when unique insights emerged. Furthermore, to guarantee the authenticity of the responses, participant anonymity and confidentiality of the information were assured (Cheng et al., 2022).

The convenience sampling approach was utilized for participant recruitment, which was carried out through social media platforms. Convenience sampling is particularly suitable for exploratory studies where the primary goal is to generate insights and to identify key factors rather than to generalize findings to a larger population. Given the limited literature on this topic, convenience sampling allowed us to efficiently gather preliminary data to inform our theoretical model and hypothesis. We set clear criteria for potential respondents: ‘You have an understanding of digital exhibitions’ and ‘You are willing to be interviewed for 10–20 min’. A total of 20 participants were interviewed, with each interview lasting an average of 15 min, achieving a 100% effective response rate. During the final interviews, no additional insights were observed, indicating that theoretical saturation had been achieved.

Data analysis

We analysed the data using an inductive methodology (Cheng et al., 2020). The data analysis procedure was structured into three rounds.

Round 1: The initial round of analysis focused on identifying key expressions related to consumers’ willingness to accept digital exhibitions. We began by thoroughly reading through the transcribed interviews to pinpoint sentences and phrases that were pertinent to our study question.

Round 2: We systematically categorized the outcomes of coding. This round of analysis allowed us to group similar sentiments and observations, which were then summarized using a set of descriptive keywords.

Round 3: In the final stages of analysis, these keywords from Round 2 were linked to higher-level theoretical frameworks derived from the literature on digital exhibitions and consumer behaviour in virtual environments. This process facilitated the development of a coherent narrative around the identified factors, shedding light on the potential relationships between constructs.

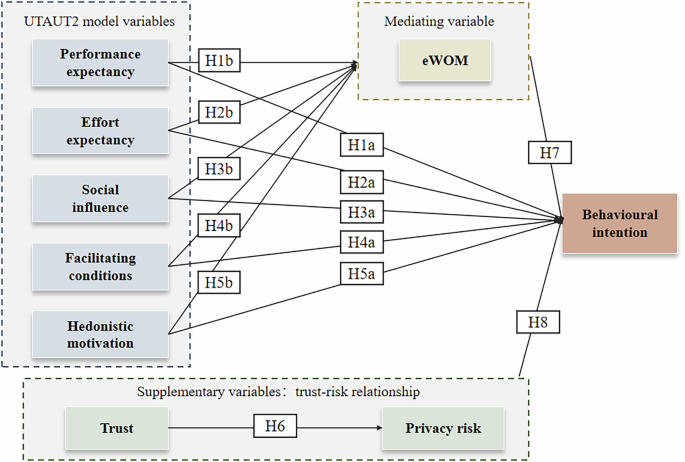

Our analysis was particularly attentive to constructs that were frequently mentioned across interviews, ensuring that the derived themes genuinely reflected the perspectives of our participants. As indicated in Table 2, the qualitative investigation revealed a number of important variables that affect consumers’ approval of digital exhibitions, including performance expectancy, trust, privacy risk, eWOM, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions and hedonistic motivation. The outcomes of the qualitative analysis could offer proof of how concepts were conceptualized and how hypothesis were developed (Cheng et al., 2020). Through a systematic comparison of our results with extant theories, we proposed a number of hypothesized connections.

Hypothesis development

UTAUT2-based relationships

The intention to employ information technology is positively affected by performance expectancy (Venkatesh et al., 2012). In this study, this refers to the perceived degree to which consumers believe that using digital exhibitions will enhance their effectiveness and facilitate the achievement of relevant tasks or goals. This encompasses their overall assessment of the utility and benefits derived from engaging with digital exhibitions. Previous studies have demonstrated that performance expectancy is a powerful predictor of behavioural intention towards digital technology (Escobar-Rodríguez, 2014; Albanna et al., 2022). The concept of performance expectancy encapsulates consumers’ inclination towards prioritizing convenience and time efficiency as significant determinants in their selection process of products or services that integrate new technological advancements. Customers are more inclined to interact with one another when they feel that there is a high level of performance expectancy and exhibit a greater propensity to recommend the service and participate in eWOM activities (Hwang et al., 2019; Loureiro et al., 2018). As one interviewee stated, ‘The digital exhibitions greatly facilitated my shopping experience, allowing me to find what I needed more efficiently. Therefore, I am very willing to recommend this service to my friends’ (Participant 8). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1a. Performance expectancy positively influences consumers’ willingness to accept digital exhibitions.

H1b. Performance expectancy positively influences electronic word of mouth.

Effort expectancy refers to the perception that using technology-related products requires minimal effort from users (Venkatesh et al., 2012). This concept assesses the complexity and user-friendliness of new technological applications. When a new technology is embraced in its early stages, effort expectancy is crucial (Ooi et al., 2018).

Effort expectancy is positively associated with AR technology adoption (Ustun et al., 2023). Customers will enjoy using a new platform when it is simple to use and navigate, which could lead to positive eWOM. An interviewee stated the following: ‘Using the digital exhibitions was straightforward and intuitive. I didn’t need to spend much time figuring out how to navigate the platform, which made the whole experience more enjoyable. I feel more inclined to use it again’ (Participant 14). Additionally, the interviewee stated, ‘When I find that the platforms associated with the digital exhibitions are easy to operate, I am willing to recommend the digital exhibitions to others’ (Participant 2). Therefore, the following hypothesis are proposed:

H2a. Effort expectancy positively influences consumers’ willingness to accept digital exhibitions.

H2b. Effort expectancy positively influences electronic word of mouth.

Social influence demonstrates how significantly an individual feels that important figures in the individual’s life deem it essential for him or her to adopt new practices (Venkatesh et al., 2012). Interactions with influential others can significantly mitigate the individual’s perceived uncertainties, risks, and anxieties associated with adopting new technologies. This perception markedly influences people’s readiness to embrace and adapt to novel platforms (Chopdar et al., 2018).

Quesnel and Riecke (2018) demonstrated that positive emotions associated with commercial products are predominantly elicited by social stimuli. Positive emotions may facilitate the sharing of information among individuals, thus leading to positive eWOM behaviour (Guo et al., 2018; Hameed et al., 2024). An interviewee stated the following: ‘Seeing familiar people share information about the digital exhibitions on social media platforms encourages me to want to experience it. If my experience is positive, I am willing to recommend it to people around me’ (Participant 7). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H3a. Social influence positively influences consumers’ willingness to accept digital exhibitions.

H3b. Social influence positively influences electronic word of mouth.

Facilitating conditions relate to how much customers perceive that technological advancements improve their ability to effectively perform a particular activity, thus providing the necessary support and resources to streamline and improve their experience (Venkatesh et al., 2012). Facilitating conditions encompass environments or organizations capable of assisting consumers in overcoming obstacles to adopting new technologies. This paper contends that, within the context of examining consumers’ willingness to embrace digital exhibitions, facilitating conditions primarily pertain to the extent to which AR, VR, and other technological infrastructures support consumers’ engagement with digital exhibitions.

In digital environments, facilitating conditions, such as ease of access and user support, have been shown to positively affect consumers’ willingness to accept and utilize new technologies (Queiroz & Wamba, 2019; Ben Arfi et al., 2021). In turn, this encouragement may result in a more positive outlook on sharing suggestions and good experiences on the internet. For example, some participants said, ‘The application of AR technology enhanced my understanding of the information and provided me with a positive experience. This new experience not only increased my satisfaction but also influenced me to write positive reviews online, encouraging others to visit’ (Participant 13). Thus, the following hypothesis are proposed:

H4a. Facilitating conditions positively influence consumers’ willingness to accept digital exhibitions.

H4b. Facilitating conditions positively influence electronic word of mouth.

Consumer happiness or the pleasure that consumers derive from engaging with technology is known as hedonic motivation, which reflects the degree of perceived fun or pleasure (Venkatesh et al., 2012). Digital exhibitions employing VR, AR and other advanced technologies represent novel experiences for most consumers. The integration of these emerging technologies enhances the interactivity and enjoyment of digital exhibitions. The theory of consumer innovativeness suggests that motivational factors constitute the foundation for consumer innovation. This perspective posits that the impetus for individuals to adopt innovative products or services is propelled by a variety of motivations, including functional, hedonic, social, and cognitive motivations. Among them, hedonic motivation is identified as a significant dimension. Meena and Sarabhai (2023) contends that consumers’ engagement with online platforms or applications is predominantly driven by ideals associated with hedonic. Hedonic motivation significantly influences consumers’ willingness and behaviour with regard to adopting new technologies and products (Kim & Hall, 2019). This sense of enjoyment and pleasure significantly affects individuals’ readiness to engage with and promote novel platforms. A participant in the interview expressed the following: ‘Exploring the digital exhibitions was genuinely enjoyable. The advanced technology there, like AR, allowed me to interact with the exhibits in ways I never thought possible’ (Participant 6). Additionally, after further questioning, the interviewee expressed a willingness to share the interesting aspects of the digital exhibitions on social media platforms. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5a. Hedonic motivation positively influences consumers’ willingness to accept digital exhibitions.

H5b. Hedonic motivation positively influences electronic word of mouth.

Trust and privacy risk

In the social sciences, trust has been extensively acknowledged as a pivotal element influencing individuals’ behaviour and the propensity to take action that can lower the perceived level of risk (Bansal et al., 2016; Zhani et al., 2022). Bryce and Fraser (2014) emphasize how crucial trust is to communication transactions, a consideration that gains heightened significance when users assess the risks associated with online communication exchanges. The absence of trust coupled with heightened perceived risk among involved parties typically leads to the abandonment of transactions (Hansen et al., 2018). Previous research has revealed that trust can reduce privacy risk (Featherman et al., 2021). As one interviewee stated, ‘The more I trust the company that offers a digital exhibition platform, the less concerned I am about my privacy risk. When I believe that the company building the digital exhibitions is reliable, it diminishes my worry about how my personal information is handled’ (Participant 17). Hence, we hypothesize the following:

H6. Trust negatively influences consumers’ privacy risk.

eWOM and behavioural intention

eWOM is acknowledged as a pivotal element in consumer behaviour, exerting a substantial influence on business performance (Babić Rosario et al., 2020). eWOM transcends the constraints of time and space, amplifying its influence via the extensive reach of the internet. According to social identity theory, consumers are likely to consider the views and experiences of their peers when making decisions. Consumers perceive eWOM communications as more reliable and beneficial than conventional commercial advertising (Filieri et al., 2018). Unlike conventional advertising, which is often seen as driven by the interests of companies, eWOM communications are perceived as genuine experiences and opinions from real users. Consequently, consumers place greater trust in these peer-generated insights, finding them more valuable for making informed purchasing decisions. The observation of positive product or service reviews on social media and other digital platforms can lead consumers to infer superior quality and satisfactory user experiences, thus enhancing their purchase intentions. One of the interviewees stated the following: ‘The positive experiences shared by others online really piqued my interest and made me feel more inclined to see what the exhibition was all about. Their endorsements made me confident that it would be worth my time’ (Participant 9). Therefore, we propose the following:

H7. Electronic word of mouth positively influences consumers’ willingness to accept digital exhibitions.

Privacy risk and behavioural intention

Within the e-commerce domain, perceived risk is the subjective anticipation of potential losses that users might encounter in their quest to achieve desired outcomes. Chopdar et al. (2018) highlighted that perceived risk is a multifaceted concept that includes informational, financial, and product risks. Information risk refers to consumers’ concerns about security and privacy. Among the various perceived risks, this study’s main focus is on privacy risk. When customers believe that there is a significant privacy risk, their willingness to adopt new technological products is likely to be diminished (Merhi et al., 2019; Ben Arfi et al., 2021). As one interviewee stated, ‘I was interested in visiting the digital exhibitions, but I hesitated because I was worried about how my personal information would be used’ (Participant 11). Therefore, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

H8. Privacy risk negatively influences consumers’ willingness to accept digital exhibitions.

Meditating influence of perceived risk

The perception of privacy risk, which is characterized as a detrimental factor, may attenuate consumers’ acceptance and diminish their subsequent purchase intentions. If trust exists among the parties involved in establishing connections, it can mitigate the cognitive subject’s anxiety regarding perceived risks and enhance the subject’s willingness to adopt new technologies (Zahid & Haji, 2019). Trust acts as a crucial buffer against the negative impact of privacy risk, providing reassurance to consumers that their data will be handled securely and responsibly. When trust is established, consumers feel more confident and less apprehensive about engaging with digital platforms, which can lead to increased acceptance and usage (Zahid & Haji, 2019). When consumers discern risk in specific behaviours or decisions, they are inclined to adopt a conservative stance to avert potential dangers. This conservative stance is a natural defensive mechanism aimed at protecting oneself from possible negative outcomes. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H9. Privacy risk significantly mediates the impact of trust on consumers’ willingness to accept digital exhibitions.

Meditating influence of eWOM

Earlier research has shown that the social value of interaction, hedonic motivation, and the fulfilment of personal interests within the community can facilitate the generation of eWOM (Motyka et al., 2018). It allows consumers to reduce uncertainty and effort by relying on peer experiences and reviews (Verma et al., 2023). Performance expectancy reflects consumers’ beliefs that digital exhibitions are useful and enhance their experience. When users perceive high utility, they are more likely to share positive feedback online, reinforcing collective perceptions of value. This may indirectly shape the behavioural intentions of others. Therefore, we propose:

H10a. Electronic word of mouth significantly mediates the effect of performance expectancy on behavioural intention.

Effort expectancy is linked to ease of use, which influences user satisfaction and their willingness to communicate that experience to others. Consumers engage with eWOM information with the anticipation of minimizing the time and effort associated with decision-making processes, thus increasing the likelihood of reaching more satisfactory outcomes (Babić Rosario et al., 2020). When digital exhibitions are easy to navigate, users are more likely to engage in eWOM, encouraging others to try the platform. Therefore, we propose:

H10b. Electronic word of mouth significantly mediates the effect of effort expectancy on behavioural intention.

The advancement of social technologies has reintroduced social interaction into the online purchasing process, transforming it into a more socially driven experience (Lho et al., 2022). Social influence can encourage users to participate in digital exhibitions, but the translation of this pressure into action is often reinforced through shared user experiences. eWOM acts as a channel where social cues become validated and amplified. Therefore, we propose:

H10c. Electronic word of mouth significantly mediates the effect of social influence on behavioural intention.

Enjoyable and emotionally engaging experiences often trigger users to share their satisfaction online (Liu et al., 2021). These hedonic experiences, when communicated through eWOM, can persuade others to participate. Accordingly, we propose:

H10d. Electronic word of mouth significantly mediates the effect of hedonic motivation on behavioural intention.

Supportive technical infrastructure may not directly affect behavioural intention but may encourage users to share their seamless experiences with others. These shared experiences, in turn, build confidence among potential users (Yadav et al., 2024). Thus, we propose:

H10e. Electronic word of mouth significantly mediates the effect of facilitating conditions on behavioural intention.

Our research model is shown in Fig. 1.

Study 2: PLS-SEM analysis

Sample and data collection

To evaluate the hypothesis, we modified the measurement instruments for the constructs (Table 3) from the literature. These instruments have been previously validated, and their reliability has been demonstrated. We disseminated an online questionnaire after a pre-test. Between April and May 2023, we garnered 367 responses. Following the exclusion of invalid responses characterized by exceptionally brief completion times, insufficient information, or overly consistent selections, 283 valid responses were retained for analysis.

Among the recovered questionnaires, the relatively balanced male‒female ratio helps ensure the validity and reasonableness of the collected questionnaires. The majority of participants fell within the 18-40 age group, representing the demographic with the highest internet usage. The study was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. For participants under the age of 18, ethical measures were rigorously applied, including obtaining informed consent from parents or legal guardians and ensuring the anonymity and confidentiality of responses. The majority of the respondents had received a college education, which likely contributed to their greater ability to understand the questionnaire items and greater receptiveness to new things (Table 4).

Data analysis

The measurement and structural model were evaluated using PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 2019). To determine the configurations of the antecedent conditions influencing the results, fsQCA was subsequently used (Ragin, 2008).

In studies with small sample sizes and data that are not regularly distributed, PLS-SEM is more suitable. Furthermore, PLS-SEM enhances modelling flexibility by accommodating complex models and formative constructs (Hair et al., 2019). Given the intricate nature of our research model, we have opted for the PLS-SEM approach. This method allows us to effectively handle the complexity and specific requirements of our study, ensuring robust and reliable results.

In daily life, results typically emerge from various antecedent condition combinations, not just a single factor, especially in situations of substantial causal complexity. The fsQCA method is uniquely well suited for dissecting these causal mechanisms, offering a configurational perspective on the interplay of causes leading to outcomes and addressing considerable causal complexity (Romero-Castro et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2023). Therefore, we applied fsQCA to supplement the findings of the qualitative method, allowing for a more in-depth analysis in this study and a more comprehensive understanding of business behaviour complexity (Navarro-García et al., 2024).

Measurement model

By employing PLS-SEM within SmartPLS 4.0, the analysis shows that the measurement model satisfies all accepted general requirements. Table 5 shows that since the standardized loading of every single item was greater than 0.7, every single item met the requirements for reliability. In addition, convergent validity was analysed on the basis of factor loadings and AVEs; each item within the variable dimensions exhibited standardized factor loadings greater than 0.6, and the AVE values exceeded 0.5, indicating strong convergent validity (Hair et al., 2019). Furthermore, as shown in Tables 6 and 7, the square root of the AVE for every variable is greater than the correlation coefficients of that variable with the other variables, and the HTMT ratios between all the variables are significantly less than 0.9. These results indicate that the variables possess strong discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Common method bias

Common method bias (CMB) arises when variance in observed data is due to the use of a common measurement instrument rather than the actual constructs being measured. It can occur when both independent and dependent variables are collected using the same method, such as a self-report questionnaire, leading to spurious correlations and misleading conclusions. To assess CMB, we used Kock’s (2015) full collinearity test. According to Kock (2015), if the variance inflation factors (VIFs) in the inner model are ≤3.3, the model is free of CMB. Our results revealed that all VIFs ranged from 1.000 to 1.678, well below the threshold, indicating that CMB is not an issue in this study and that the observed relationships are free from methodological artefacts.

Structural model and hypothesis testing

The variance inflation factor (VIF) is used to examine multicollinearity. Table 7 shows that the VIF values are notably well below the critical threshold of 3, ranging from 1.000 to 1.678 (Hair et al., 2019). This observation suggests that multicollinearity is not a concern in this analysis.

We used 5000 resamples of bootstrapping for hypothesis testing. As displayed in Table 8, effort expectancy (β = 0.130, p < 0.05), eWOM (β = 0.182, p < 0.01) and privacy risk (β = -0.278, p < 0.001) significantly influence behavioural intention, supporting H2a, H7 and H8. Performance expectancy (β = 0.049, p > 0.05), social influence (β = 0.054, p > 0.05), facilitating conditions (β = 0.034, p > 0.05), and hedonistic motivation (β = 0.089, p > 0.05) have no significant effect on behavioural intention. Thus, H1a, H3a, H4a and H5a are not supported.

To examine the mediating roles, we adopted the bootstrapping method (Roldán et al., 2017). As shown in Table 9, the indirect effects indicate that eWOM acts as a major mediator in the relationship between performance expectancy (t = 2.057, p < 0.05), social influence (t = 2.060, p < 0.05), effort expectancy (t = 2.187, p < 0.05), and BIs. However, the mediating effects on the relationship between hedonistic motivation (t = 1.662, p > 0.05) and FCs (t = 0.785, p > 0.05) with behavioural intention are not significant. The significant mediating role of privacy risk in the relationship between trust (t = 3.732, p < 0.001) and behavioural intention is also confirmed in this study.

Study 3: fsQCA analysis

The initial phase in the fsQCA process is data calibration. This process entails converting variables into fuzzy sets by assigning them set membership scores that range from 0 to 1. Here, a score of 1 represents full membership in the set, whereas a score of 0 denotes full non-membership (Pappas & Woodside, 2021). For this study, the thresholds for full membership, the crossover point, and full non-membership were set at the 95th, 50th, and 5th percentiles of the original data, respectively. The data calibration results are shown in Table 10.

Before carrying out a sufficiency analysis, it is essential to perform a necessity analysis to explain that a single independent variable alone cannot constitute a necessary condition for explaining the dependent variable. Doing so involves determining whether there are necessary antecedent conditions that produce the outcome variable. According to Fiss (2011), when a condition has a consistency score greater than 0.9, it is considered required (Wang et al., 2021). As shown in Table 11, the consistency of each antecedent condition is less than 0.9, indicating that an output behavioural intention cannot be produced by a single condition.

By constructing a truth table, this paper further explored the sufficiency of different configurations of multiple antecedent condition variables in shaping consumer behavioural intention. To prevent distractions from less significant configurations, this study used a frequency cut-off of 3 (Pappas & Woodside, 2021) and a consistency cut-off of 0.8 (Ragin, 2008).

The findings derived from the fsQCA, as presented in Table 12, reveal two configurations for behavioural intention. The overall solution consistency and solution coverage exceeded the thresholds recommended by Ragin (2008), specifically 0.75 and 0.25, respectively. Furthermore, the consistency of each solution exceeded 0.8, affirming the sufficiency of all identified solutions. Additionally, the coverage of every solution was greater than zero, demonstrating its empirical relevance (Ragin, 2008).

For behavioural intention, effort expectancy (EE), social influence (SI), hedonistic motivation (HM) and eWOM are present in both configurations, and privacy risk (PR) is absent in both configurations, indicating their importance in the analysis. In configuration 1, high behavioural intention are associated with the presence of EE, SI, and HM, alongside eWOM. The absence of PR also characterizes this configuration. Configuration 2 for high behavioural intention also includes EE, SI, and eWOM, similar to configuration 1. However, facilitating conditions (FCs) and trust (TR) are also present, indicating additional pathways that contribute to behavioural intention.